In Search of Bitto

Chris Munsey, Fromager at Murray's and cheese adventurer spent several weeks this fall exploring northern Italy and tracking down new and interesting cheeses (some of which are now being featured at Murray's!). The story starts up in the mountains of Lombardy...

The trip had sounded ideal back in New York- a visit to a small cheesemaking operation located in the Italian Alps, to observe the creation of Bitto, a traditional alpine cheese that Murray's was about to introduce to New York. I had met my Italian friend Vitto in Milan and drove north along a road just a hairswidth wider than our compact Fiat to the small town of Introbio. Here we met with Giuseppe a representative of one of our Italian cheese distributors who supposedly had information on where to find the cheesemaker, Marco Giacomini. However, the real situation was shaping up differently.

Giuseppe stared at me gravely through his rectangular chrome rimmed glasses: "Signore, after reaching Chiavenna you must hike for at least three hours up into the mountains. It has been raining for days and might still be raining. I'm not sure about the directions. I don't know if there is anywhere to stay up there either. "

Was he serious? "Well isn't there a path up to cheesemaking hut? How do you get there when you visit Marco?"

"Me? Oh I don't know, I've certainly never been there myself."

So here we are: a drive to the village of Chiavenna ahead of us and then a three hour hike up a mountain; possibly in the rain. And it was already three o'clock in the afternoon. Our chances of getting lost up on a remote mountain looked pretty good, but this would be our only chance to see Bitto being made. My enthusiasm for cheese won out over good sense.

"Great! Giuseppe, you have been an immense help, thanks so much"

Vitto and I set out for the car to muddle things out on our own. Just as we were about to drive off, Giuseppe ran out and handed me a small piece of paper. "This is Marco's cell phone number. It doesn't usually work, since he is so far up in the mountains, but just in case…" explained Giuseppe and cheerfully bid us on our way.

We zipped along the narrow, winding road towards Chiavenna, a steep cliff on one side and a dizzying drop-off one thousand feet straight down to the valley below us on the other. As the sole Italian male in the car, Vitto was driving, while I tried to call Marco, the cheesemaker. On the third try, the number worked and a loud friendly voice greeted me: "Pronto?".

Luckily for us, almost everything we had been told before was a gross exaggeration of the truth.

Marco was happy to have us visit his calecc (the small stone cabins where cheesemakers stay during the summer to make Bitto). There was even a rifugo (a rustic mountain pension) en route where we could stay. We arrived in the picturesque village of Chiavenna and began to hike. The sun was shining and the path to the calecc was meticulously well marked. Benches strategically placed along the way allowed one to rest and take in the gorgeous green valley.

Just as the sun was setting, we came to the rifugo, one of approximately 10 ancient stone buildings in a little village perched on the side of the mountain. The proprietors of the rifugo were a pleasant couple who cooked up a feast: buckwheat tagliatelle and freshly picked porcini mushrooms, followed

by a hearty venison ragu, delicately steamed balls of polenta with sage and a dark, rustic Valtellina wine. To finish the meal, a board was laid out with slices of a fragrant, deep golden hued cheese and pears. Bitto produced on this very mountain! I took my first bite and became immediately addicted to this rich, nutty, tangy cheese. New York was going to love this cheese!

The rest of the evening was spent up on the rooftop porch of the rifugo, gazing at the stars, sipping the throat-burning local grappa and pondering what other fantastic discoveries would surprise us along the way.

After literally falling into unconsciousness the night before (nothing like a little grappa to help fall asleep) my alarm clock woke me with a start. It was still pitch dark out and up at the Calecc, Marco was probably already started with the morning milking. Vito and I stumbled groggily from bed and went down to drink steaming, thimble-sized cups of strong dark espresso, before setting out to find our first authentic Italian cheesemaker.

The sun quickly burned through the morning mist as we climbed up the steep trail. We crested a ridge and right in the middle of the path was a cow, tranquilly munching away. We must be getting close!

We crossed two narrow fast-moving rivers, past an old abandoned stone dwelling and there in front of us was the calecc. Situated in a natural amphitheater shaped clearing, ringed with steep cliffs, the little stone hut almost blended in with the surrounding boulders.

Marco, a sturdy, ruddy faced young man emerged from the door of the cheesemaking room and greeted us: "Ciao, come on up!"

He, his wife and another farmhand had just finished milking their seventy Brown Swiss cows, the traditional bovine breed used to make Bitto in this area. In order to meet DOP (protected denomination of origin) status as an alpine cheese, Bitto must be made at an altitude of at least 1,500 meters and can only be produced from June until September. 700 liters of milk from the morning milking were being heated in a large shiny copper kettle to produce what would be the last wheels of Bitto produced this season.

We watched as Marco expertly cut the curd with a traditional wooden knife until it was a mass of pea-sized chunks. He explained that it was very important to cut the curd into very small pieces in order to obtain a dense, smooth compact cheese - a sign of a properly made Bitto.

He then scooped large amounts of curd into cheesecloths and pressed them into molds. A flat wooden board was set upon the curds and then a heavy rock followed to press the excess whey out of the curds.

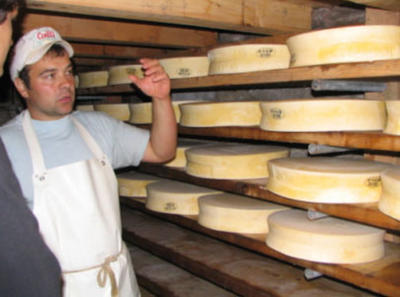

The wheels of fresh cheese would be soaked in salt brine overnight and matured upon oak boards for 70 days. At least one to two years of additional aging would result in a top quality Bitto. Some connoisseurs prefer Bitto at a much older stage and wheels that have been aged for up to 10 years can sometimes be found!

After he was finished making cheese, Marco pointed out the markings on the rind of the cheese, which indicate that exacting standards to qualify for DOP. A long busy summer for Marco was drawing to a close. Tomorrow he would lead the cows down from the mountain to the valley, where they would spend the cold winter months.

Tomorrow Vitto and I would be in Piedmont near the French border, in search of another amazing Italian cheese currently being featured at Murray's.

to be continued…

<< Home